The extensive use of biochar on farms in some regions could reduce consumption of water for irrigation by half, according to new research from Rice University. The study revealed that sandy soils benefit the most by retaining water and reducing the need for irrigation.

Rice researchers said the 50 percent water savings is the best-case scenario for some regions, representing a significant immediate savings to go with the established environmental benefits of biochar, such as the long-term sequestration of carbon and nitrogen on farmland.

The open-access study appears in the journal GCB-Bioenergy.

Biochar, which is basically charcoal produced through pyrolysis, the high-temperature decomposition of biomass including straw, wood, shells, grass and other materials, has been the subject of extensive study at Rice and elsewhere as the agriculture industry seeks ways to enhance productivity, sequester carbon and preserve soil.

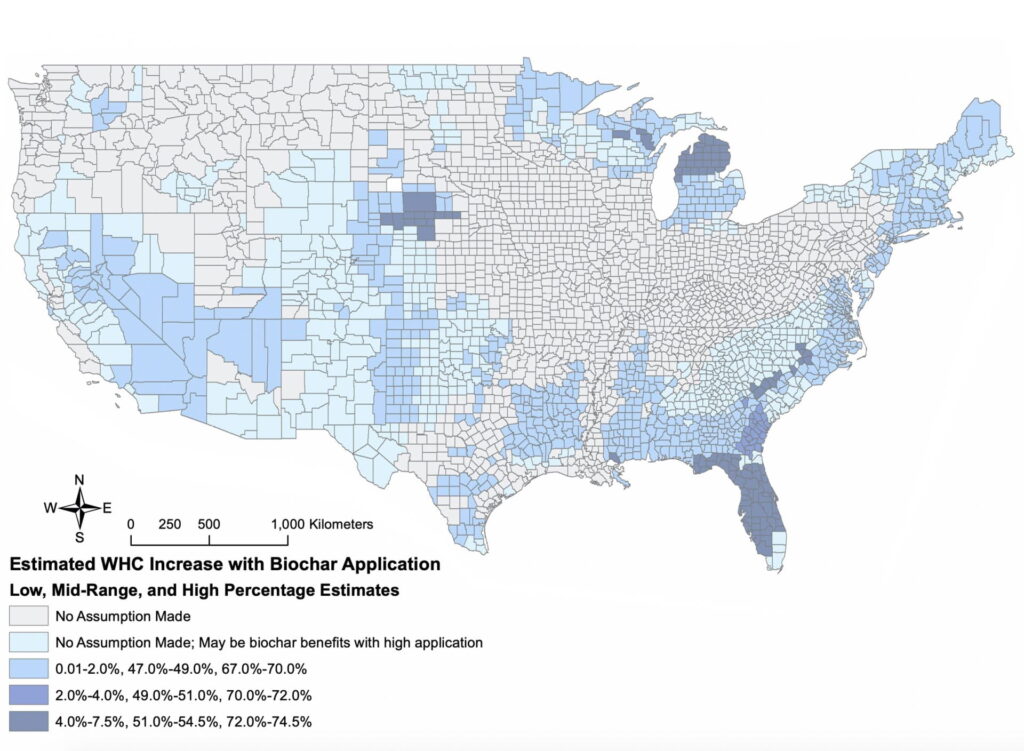

A map shows low, mid-range and high estimates for theoretical water-holding capacity changes in soil with the addition of biochar. A study by Rice University scientists showed how biochar can help curtail excess irrigation in agriculture, depending on the type of soil and biochar characteristics. Courtesy of the Masiello Lab

The new model built by Rice researchers explores a different benefit, using less water.

“There’s a lot of biochar research that focuses mostly on its carbon benefits, but there’s fairly little on how it could help stakeholders on a more commercial level,” said lead author and Rice alumna Jennifer Kroeger, now a fellow at the Science and Technology Policy Institute in Washington, D.C. “It’s still an emerging field.”

The study co-led by Rice biogeochemist Caroline Masiello and economist Kenneth Medlock provides formulas to help farmers estimate irrigation cost savings from increased water-holding capacity with biochar amendment.

The researchers used their formulas to reveal that regions of the country with sandy soils would see the most benefit, and thus the most potential irrigation savings, with biochar amendment, areas primarily in the southeast, far north, northeast and western United States.

The study analyzes the relationship between biochar properties, application rates and changes in water holding capacity for various soils detailed in 16 existing studies to judge their ability to curtail irrigation.

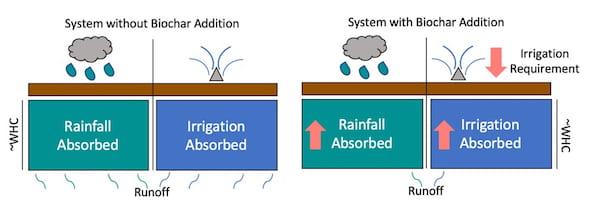

The researchers defined water holding capacity as the amount of water that remains after allowing saturated soil to drain for a set period, typically 30 minutes. Clay soils have a higher water holding capacity than sandy soils, but sandy soils combined with biochar open more pore space for water, making them more efficient.

Water holding capacity also is determined by pore space in the biochar particles themselves, with the best results from grassy feedstocks, according to their analysis.

In one comprehensively studied plot of sandy soil operated by the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s Agricultural Water Management Network, Kroeger calculated a specific water savings of 37.9 percent for soil amended with biochar. Her figures included average rainfall and irrigation levels for the summer of 2019.

The researchers noted that lab experiments typically pack more biochar into a soil sample than would be used in the field, so farmers’ results may vary. But they expressed hope their formula will be a worthy guide to those looking to structure future research or maximize their use of biochar.

More comprehensive data for clay soils, along with better characterization of a range of biochar types, will help the researchers build models for use in other parts of the country, they wrote.

“This study draws attention to the value of biochar amendment especially in sandy soils, but it’s important to note that the reason we are calling out sandy soils here is because of a lack of data on finer-textured soils,” Masiello said. “It’s possible that there are also significant financial benefits on other soil types as well; the data just weren’t available to constrain our model under those conditions. Nature-based solutions are gaining traction at federal, state and international levels. Biochar soil amendment can enhance soil carbon sequestration while providing significant co-benefits, such as nitrogen remediation, improved water retention and higher agricultural productivity. The suite of potential benefits raises the attractiveness for commercial action in the agriculture sector as well as supportive policy frameworks.”

Rice alumna Ghasideh Pourhashem, a nonresident faculty scholar at the Center for Energy Studies (CES) at Rice’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, is co-author of the paper. Masiello is the W. Maurice Ewing Professor, a professor of Earth, environmental and planetary sciences and a faculty scholar at the CES. Medlock is the James A. Baker, III, and Susan G. Baker Fellow in Energy and Resource Economics at the Baker Institute, senior director of the CES and an adjunct assistant professor of economics.

The Rice Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences and the Rice Shell Center for Sustainability supported the research.

You can read the study at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gcbb.12765.

Follow us on social media:

Be the first to comment on "Biochar could cut farms’ water use by half, study says"